Evening Wear

(Note: click on most of these images for a larger view)

Gentleman's evening wear changed hardly at all from around 1860 until the turn of the century when the Tuxedo made its gradual march toward respectability.

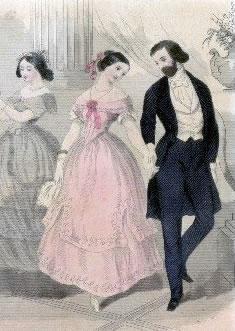

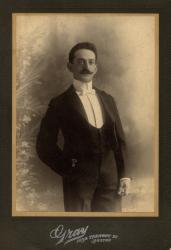

From about 1860 to the 1920s, proper evening wear was a unvarying uniform of black tail coat, small white tidy bow tie, black or white low-cut vest with shawl lapels (there seems to have been some personal latitude in selecting vest hue--black being the most common) and black trousers, with a white, heavily starched shirt. The only thing that changed was the collar, which followed the current fashion.

Ironically, civilian evening attire was far more uniform and standardized than the military uniforms of the time, which were quite colorful, splendid and infinitely varied - with a variety of orders of dress (full dress, levee, mess etc.) specified for various festive occasions. This is far too complex an issue to tackle here, and I will limit myself to addressing the comparatively dull and colorless choices available to the civilian gentleman.

Starting in about 1800, black gradually displaced color in mens' evening wear and by the 1840s was fairly dominant. Knee pants with black silk stockings were an essential evening accessory until 1850s when long trousers finally took over. Up until the 1850s, the tie could be black or white, but by the '60s, white or off-white was the most common choice.

Through this whole period, and well into the 20th Century, evening pumps, rather than laced shoes were the normal choice for foot wear. They are still available today from some upscale mens' shops and are usually referred to as "Opera Pumps".

Outdoors, evening wear would be worn with a black top hat and a black cape or overcoat.

White or pale gloves were an essential accessory, especially when dancing, as touching a lady with bare hands was not only a bit crude, but one's sweat could soil her gown.

White or pale gloves were an essential accessory, especially when dancing, as touching a lady with bare hands was not only a bit crude, but one's sweat could soil her gown.

Black evening vests were nearly always of fine wool. White vests could be of cotton, linen, light weight wool, silk or any fabric capable of being white. They might have a pattern woven in, but the pattern would generally be white-on-white.

Colorful vests, with or without garish prints, such as one now sees in a formal wear or "western wear" shop, were not worn with evening attire.

Buttons on black coats and vests were usually black, flat fronted and covered with silk - either plain or in a pattern. White vests usually had white buttons.

Shirt studs might be gold, diamond, or otherwise splendid; but the buttons on the vest and coat tended to be very subtle and subdued.

"A gentleman retains his 'walking' or 'morning' attire until six or seven o'clock when he dresses for the evening"

"Everybody's Book" 1893

"The evening or full dress suit for gentlemen is a black dress-suit--a 'swallow tail' coat, the vest cut low, the cravat white, and kid gloves of the palest hue or white. The shirt front should be white and plain; the studs and cuff buttons simple. Especial attention should be given to the hair, which should be neither short nor long. It is better to err on the too short side, as too long hair savors of affectation, destroys the shape of the physiognomy, and has a touch of vulgarity about it. Evening dress is the same for a large dinner party, a ball or an opera. In some circles, however, evening dress is considered to be an affectation, and it is well to do as others do. On Sunday, morning dress is worn, and on that day of the week no gentleman is expected to appear in evening dress, either at church, at home or away from home. Gloves are dispensed with at dinner parties, and pale colors [of gloves] are preferred to white for evening wear."

"Our Deportment" 1882

"The attire in which a gentleman can present himself in a ball room admits of so little variety, that it can be described in a few words.

He must wear a black dress coat, black trousers and a black vest, and a black or white necktie and kid gloves, and patent leather pumps.

This is imperative, the ball suit should be of the very best cloth and of the latest style as to cut. The vest should be cut low, so as to disclose an ample shirt front. Small gold or diamond studs may be used with effect. Much display of jewelry is a proof of bad taste. A handsome watch chain with perhaps the addition of a few costly trifles suspended to it, and a set of shirt studs, are the only adornments of this kind that a gentleman should wear. Perfume should only be used for the handkerchief, and should be of the very best and most delicate character."

"Prof. M. J. Koncen's quadrille call book and ball-room guide" 1883

"When a gentleman is invited out for the evening, he is under no embarrassment as to what he shall wear. He has not to sit down and consider whether he shall wear blue or pink, or whether the Joneses will notice if he wear the same attire three times running. Fashion has ordained for him that he shall always be attired in a black dress suit in the evening, only allowing him a white waistcoat as an occasional relief to his toilette. His necktie must be white or light colored. An excess of jewelry is to be avoided but he may wear gold or diamond studs, and a watch chain. He may also wear a flower in his buttonhole, for this is one of the few allowable devices by which he may brighten his attire.

"When a gentleman is invited out for the evening, he is under no embarrassment as to what he shall wear. He has not to sit down and consider whether he shall wear blue or pink, or whether the Joneses will notice if he wear the same attire three times running. Fashion has ordained for him that he shall always be attired in a black dress suit in the evening, only allowing him a white waistcoat as an occasional relief to his toilette. His necktie must be white or light colored. An excess of jewelry is to be avoided but he may wear gold or diamond studs, and a watch chain. He may also wear a flower in his buttonhole, for this is one of the few allowable devices by which he may brighten his attire.

Plain and simple as the dress is, it is a sure test of a gentlemanly appearance. The man who dines in evening dress every night of his life looks easy and natural in it, whereas the man who takes to it late in life generally succeeds in looking like a waiter."

Plain and simple as the dress is, it is a sure test of a gentlemanly appearance. The man who dines in evening dress every night of his life looks easy and natural in it, whereas the man who takes to it late in life generally succeeds in looking like a waiter."

The Ball Room Guide. 1860

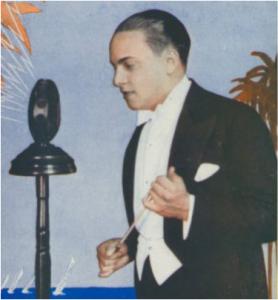

The Tuxedo

Beginning around 1900, younger men starting championing a new type of formal wear: the Tuxedo (in Britain, the "Dinner Jacket"). It was a blending of the evening tail suit and the day sack suit and featured a shawl collared jacket with a squared cut. It started out in the 1890s as a relaxed choice for all-male gatherings, with the tails worn in mixed gatherings. This changed gradually over the next few decades. Double breasted variations also existed, and followed the fashionable cut of the time for double breasted sack coats.

The illustration to the right is from a 1906 Sears Catalog, but is a common cut for Tuxedos up through the 1930s. Click on it for a larger image.

The tux was invariably worn with an evening vest, usually black, and, usually, a black tie though the rules were still in flux and some examples of deviation from the Tux-with-black-vest-and-tie rule can be seen up through the 1930s.

The advance of the Tuxedo required an adjustment in the way evening gatherings were characterized. Starting around the 1920s, if an event was fairly informal, and Tuxedos were suitable, it would be described as "black tie" and if it was a very formal affair, and only tails were suitable, it was described as "white tie".

One might see at a "black tie" affair gentlemen who did not own a tux wearing tails with a black vest and black tie - though many older gentlemen stuck to their Victorian conventions and wore full white tie and tails to any evening function regardless of the tie mentioned on the invitation. Further, as the "black tie/white tie" distinction became the norm, it became a convention to wear a white vest with tails and a black vest with a tux. Prior to that, a black vest was a far more common choice when wearing tails.

In the 1920s, white dinner jackets started to appear for wear in spring and summer. They were worn with a white shirt and black trousers, vest and tie. They were made of wool or cotton and were cut in a manner identical to the single or double-breasted black tuxedo/dinner jackets of the time.

It was a common practice to wear a black pocket square with a white jacket, as opposed to the white one worn with all black jackets.

Young men tested the limits of evening wear conventions in the 1920s & '30s, with things like cummerbunds, colored jackets or military style mess jackets, but none of these gained broad acceptance until much later.

20th Century Changes to the Cut of Evening Tails

Through the entire second half of the 19th Century, and up until the 1920s, evening tails retained the same basic cut, and this cut is different from that of the tails available in most formal wear or "vintage clothing" shops.

Through the entire second half of the 19th Century, and up until the 1920s, evening tails retained the same basic cut, and this cut is different from that of the tails available in most formal wear or "vintage clothing" shops.

The primary difference is the cut of the waist on the coat and vest. The 19th Century style has the lower hem of the coat and vest cut parallel to the ground (see the illustrations above). The later cut, from the 1920s on, tapers downward toward the front to accentuate or simulate a slim waist and to change the cylindrical sense of the earlier cut.

Further, from the 1920s on, the trousers are cut fuller in a style that follows the fashion for all men's wear of the time, with pleats becoming a marked feature in the 1930s and '40s.

19th Century trousers, while they might vary a bit with the fashionable cut of the day (cut fuller in the 1860s than the 1880s), were generally of a very simple straight, high waisted cut.

The side stripes, on the outer leg seams, which were seen from time to time earlier but were not the norm; became a standard feature by the '20s and '30s.

The center crease, pressed in to the trousers, was not generally seen in any sort of mens wear, formal or otherwise, until the 1890s, when the use of steam pressing machines by cleaners became widespread, and the knife-edge crease became easy to do and a sign of a well turned out gentleman.

I particularly recommend "The Black Tie Guide" to those wishing to know more about men's formal wear.