Calling Cards for Gentlemen

"To the unrefined and underbred, the visiting card is but a trifling bit of paper; but to the cultured disciple of social law, it conveys a subtle and unmistakable intelligence. Its texture, style of engraving, and even the hour of its leaving combine to place the stranger, whose name it bears, in a pleasant or a disagreeable attitude..."

Our Deportment, 1881

Visiting cards, or calling cards, were an essential accessory to any 19th Century middle class lady or gentleman. They served as tangible evidence of meeting social obligations, as well as a streamlined letter of introduction. They also served as an aid to memories which were no stronger then than they are today. The stack of cards in the card tray in the hall was a handy catalog of exactly who had called and whose calls might need to be returned. They did smack of affectation however, and were not generally used among country folk or working class Americans. Business cards on the other hand, were widespread among men and women of all classes with a business to promote. There was a rigid distinction between business and visiting cards, and it was considered to be in very poor taste to use a business card when making a social call. A business card, left with the servants, could imply that you had called to collect a bill.

The basic gentleman's card. It could even be hand written if his penmanship was good.

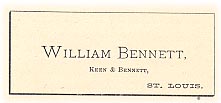

A military man's card. The "USA" stands for United States Army. An officer could also list his unit (e.g. "8th US Infantry") or ship. Army lieutenants and Naval officers under the rank of lieutenant would not put their rank in front of their names, but put it in small type in the lower left corner (e.g. "Lieutenant, USA", or "Master, USN").

A business card. It is made so by the name of his firm under his name.

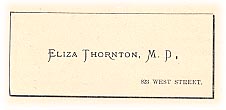

A physician's card. This is, in fact, the card of a female doctor, but is identical in form to that of a man. Doctors, lawyers, clergymen and military officers needed only one card for both business and social obligations, and included their titles on the card. The address is optional on all forms of card. |

"Callers should always be provided with cards. A gentleman should carry them loose in a convenient pocket; but a lady may use a card case. No matter how many members of the family you call upon, you send in but one card. Where servants are not kept, and you are met at the door by the lady herself, of course there is no use for a card. If you call upon a friend who has a visitor, send in but one card; but if they are not at home, leave a card for each" "Calls of pure ceremony are sometimes made by simply handing in a card" "When a stranger arrives in the city, he should send his card, with directions, to those whom he expects to call upon him. Otherwise his presence might remain for some time unknown. If a stranger of your own profession comes to the city, you should call upon him even though you do not know him." "A card may be made to serve the purpose of a call. It may be sent in an envelope, or left in person. In the latter case, one corner should be turned down if for the lady of the house. Fold the card in the middle if you wish to indicate that the call is on several, or all of the members of the family. Leave a card for each guest, should any be visiting at the house" "A card enclosed in an envelope for the purpose of returning a call made in person, expresses a desire that visiting between the parties be ended. When such is not the intention, cards should not be enclosed in an envelope."

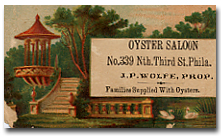

This colorful thing is a Trade Card. Cards like this would be handed to potential customers, left lying about in conspicuous places, and distributed to private residences of potential customers. It would be rather tacky to use it in lieu of a proper calling card (which isn't to say it wouldn't be done) "A man never carries or leaves the cards of any other man, nor can he assume any of the responsibilities or etiquette relating to the cards of any of his feminine relatives or friends. Men never presumed to crease or bend their cards,when such habits were in fashion, and they do not do so today." Correct Social Usage, 1903 |