Faro or Bucking the Tiger

Faro is an old game, with roots going back to the 15th Century and a game called "Basset". It attained its modern form at the court of Louis XIV. Despite this distinguished pedigree, its appeal in 19th Century America ran to all classes of society, from the banker to the '49er and was commonly called, among the "baser sort", "Bucking the Tiger".

Faro is an old game, with roots going back to the 15th Century and a game called "Basset". It attained its modern form at the court of Louis XIV. Despite this distinguished pedigree, its appeal in 19th Century America ran to all classes of society, from the banker to the '49er and was commonly called, among the "baser sort", "Bucking the Tiger".

Faro is not much played today, as it is a banking game and gambling houses tend to favor games where the odds are more clearly in favor of the house. In an honest Faro game, the punter's chances are just a little short of even of coming out ahead. Most dealers skewed those odds in their favor with some quite remarkable card shuffling and other ingenious ways of cheating. I won't go into that here however, but will assume that your table is a rare exception, and is completely on the square.

Equipment

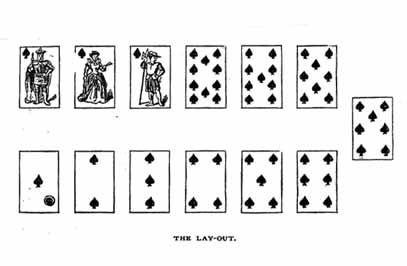

In its most basic form, the Faro table is a long rectangle (perhaps two feet by one and a half) It is covered in green felt, and laid upon this felt is the "lay-out". This is a complete suit of Spades, glued to the table and lacquered to keep them from dog-earing. The cards are laid out in two rows, running left to right. The Ace through Six is on the lower row (nearest the dealer's side of the table), the Seven is on the far right of the rows, mid way between the upper and lower row, and the Eight through King is on the upper row. This is the basic table. There are numerous refinements, which add to the class, but also to the complexity of construction.

These could include the following:

1. A raised divider, running about 8" from the edge of the table, on the player's side, to clearly delineate the players' pots from their wagers (the pot is on their side, the wager in on the dealer's side). This is not necessary if the Faro table is a separate small table set on a larger table.

2. A spring-loaded box to hold the cards. The spring ensures that the top card is always pressed against the top rim of the box, regardless of how many cards are in the box. The box has a rim to hold the cards in place, but no top. The face of the top card is visible to all players.

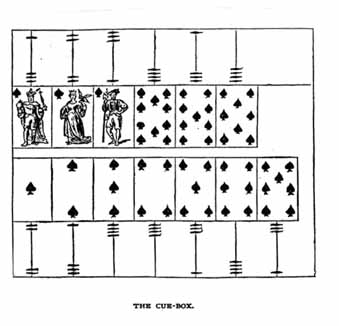

3. A "cue box" or "case keeper". This is the most complicated part of the Faro rig. It is constructed something like an abacus, with the image of each card in the Spade suit in the middle of the frame. A rod leads out of each card and on the rod is four counters. The dealer uses this to keep track of the cards which have been pulled. Each time a card his pulled, regardless of suit, he moves one counter to the far side of the rod.

4. A space marked "High Card" or "H.C." on the back edge of the table (nearest the Dealer). When this is present, the Punters may place wagers here to bet on whether the winning card (the second card drawn) will be higher than the losing card (the first card drawn). If they win, they are paid off one-to-one. They may "copper" this bet (see below) to reverse it. The High Card option dates from the last quarter of the 19th Century.

5. Chips (more commonly called "Checks") to indicate bets, though checks can be dispensed with and money placed directly on the layout. It is easiest for the Dealer if each Punter has checks of a different color or design. Colored checks can be placed on top of a bet to indicate the owner.

The cards used in Faro are a standard, familiar 52 card "French" Deck (Hearts, Diamonds, Spades, Clubs etc.)

The Game:

The Dealer's deck is placed face down on the table or face up in the Card Box.

The game commences with each player (called a "punter") laying wagers on the card images on the Faro table.

If the wager is placed directly over the card image, the Punter is wagering on only that card. A player may wager on two cards by placing his wager mid-way between two card images. He may place a single wager upon four cards by placing the wager between four of them

A Punter may place as many separate bets as he wishes or can afford.

The Dealer discards the top card (the "Soda Card"). The Dealer then wins any wagers, placed on the next card displayed (e.g. if the card should be an Ace, the Dealer collects all wagers placed on the Ace). The first card, which wins for the dealer is called the "losing card.".

The Dealer discards that card, revealing the next card. If that card is (for example) a Five, he pays off all wagers which had been placed on the Five. The second card, which wins for the Punters, is called the "winning card." The payoff is one-to-one. A dollar bet wins a dollar.

This concludes a single "Turn". In the interval between turns, the Punters may place additional wagers or increase existing ones, or move wagers from one card to another. New players may also join the game between the turns and players who still have money/chips on the table, may withdraw their wagers and either leave the game or sit out one or more turns.

The game continues in Turns, with the first draw going to the Dealer and the second to the Punters, until the deck is exhausted. The strategy lies in keeping track of which cards have been pulled. The players may watch the Cue Box (if one is present) and/or make written notes to aid their memories (the cue box may be worked by the Dealer, one of the Punters or the Dealer's Assistant, called the "Lookout"). When the Dealer gets to the bottom of the deck, the deck is reshuffled, cut and replaced, face up on the table. A Faro game has no real ending, and can continue indefinitely, with new players entering between turns and old players being wiped out or cashing out.

Coppering

The Punters have the option of "Coppering" a bet. This means placing a copper token (traditionally a Penny) on top of the bet. A Coppered bet wins on the first card, and loses on the second (the opposite of a usual bet).

Calling the Turn/Last Call:

When someone has been keeping track of the cards played (that is what the Cue Box is for), and the players become aware that they are down to the last three cards in the deck, any Punter has the option of "calling the turn". To do this, he must name the three cards remaining (not difficult if the Cue Box has been used properly), and the order in which they will be pulled. If he gets it right, he wins his bet. If he gets it wrong, he loses. As in all other aspects of Faro, suit is immaterial. If a player calls the turn successfully, he is paid off four-to-one. If two of the three cards are the same denomination (called a "cat"), then the winner is paid off only two-to-one. If all three cards are the same (highly unlikely), then the turn may not be called.

Splits:

If the first and second card are of the same denomination, or if the Punter has wagered the same stake on two cards, and one loses while the other wins, then the house only takes half the losing bet. If the amount cannot be cleanly divided in two, the difference goes to the dealer.

The Cue Box

The Cue Box (also called the "Case Keeper") is used to keep track of the turning of the cards. It may be operated by the Dealer, the Lookout, or, most commonly, by one of the more sober punters. Each time a card is played, one of the disks for that card is moved. A proper game of Faro must involve keeping an accurate track of the cards played, and if a Cue Box is not present, then the players must "Keep Tabs" by tracking the cards with a paper and pencil. This is necessary for the following reasons:

1. It allows players to bet only on cards that are likely to turn up.

2. It makes it possible to call the turn at the end.

3. The House customarily collects all bets remaining on the table after the last card is turned.